| 规格 | 价格 | 库存 | 数量 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10mg |

|

||

| 25mg |

|

||

| 50mg |

|

||

| 100mg |

|

||

| Other Sizes |

|

| 靶点 |

δ-opioid receptor ( IC50 = 2.73 nM ); μ-opioid receptor ( IC50 = 5457 nM ); δ-opioid receptor) ( Ki = 1.78 nM ); μ-opioid receptor ( IC50 = 881.5 nM ); κ-opioid receptor ( IC50 = 441.8 nM )

|

|---|---|

| 体外研究 (In Vitro) |

SNC80 选择性激活 HEK293 细胞中的 μ-δ 异聚体,EC50 为 52.8 nM。 SNC80 在共表达 μ-和 δ-阿片受体的细胞中表现出比单独表达 δ-阿片受体或共表达 δ-和 κ-阿片受体的细胞更高的活性[4]。

本研究调查了SNC80的药理学,这是一种非肽配体,拟在体外和体内作为选择性δ激动剂。SNC 80能有效抑制小鼠输精管的电诱导收缩,但不能抑制豚鼠离体回肠的收缩(IC50值分别为2.73 nM和5457 nM)。δ选择性拮抗剂ICI 174864(1μM)和μ选择性拮抗剂CTAP(1μm)在小鼠输精管中的SNC 80 IC50值分别增加了236倍和1.9倍。在小鼠全脑试验中,SNC 80优先与[3H]萘屈吲哚标记的位点(δ受体)竞争,而不是与[3H]DAMGO(μ受体)或[3H]U69593κ受体标记的位点竞争。μ/delta和kappa/delta位点的SNC80的Ki值计算值之比分别为495倍和248倍,这表明该化合物在放射性配体结合分析中具有显著的δ选择性。[2] 在单独或共表达阿片受体的异源HEK293细胞中检测SNC80,这些共表达细胞系是通过共免疫沉淀建立功能性异聚体的。先前为确定阿片受体激活而建立的内部钙释放[Ca2+]i测定用于确定SNC80诱导的受体激活的选择性功效。在这项阿片类药物疗效测定中,嵌合Δ6-Gqi4-myr蛋白将阿片受体激活转变为Gq反应(细胞内钙的释放),这是通过荧光测量的。重要的是,与[35S]GTPγS测定中的阿片类药物疗效相比,[Ca2+]i测定中的类药物疗效产生了相似和一致的结果,提供了一种方便的、非放射性的全细胞疗效测量方法。SNC80在HEK293细胞中选择性激活μ-δ异聚体,EC50=52.8±27.8 nM(SEM)(图3),平均峰值ΔRFU效应为746±83(SEM),n=3(12)。表达其他阿片受体的细胞被激活的能力要低得多。在这方面,SNC80在仅表达δ-阿片受体的细胞中的效力至少比共表达μ-δ异聚体的细胞低100倍。[4] 本研究中来自完整HEK-293细胞的体外疗效数据支持了SNC80的主要靶点是异聚体μ-δ受体的概念。如图3和图S1“支持信息”所示,SNC80在共表达μ-和δ-阿片受体的细胞中的活性明显高于单独表达δ-阿片受体或共表达δ-和κ-阿片感受器的细胞。鉴于这些受体之间存在物理关联的证据,这意味着μ-δ异聚体被SNC80选择性激活,特别是因为单表达的δ受体不会产生强效激活。这些发现,再加上报告的SNC80对μ-受体的低结合亲和力,4表明它靶向μ-δ异聚体的δ-原聚体,从而导致复合物的激活[4]。 |

| 体内研究 (In Vivo) |

SNC80(10 mg/kg;腹腔注射;一次;C57BL6/J 小鼠)治疗显着减轻了过度使用舒马曲坦引起的异常疼痛[1]。动物模型:雄性和雌性C57BL6/J小鼠(20-30g)注射舒马普坦[1] 剂量:10mg/kg 给药方式:腹腔注射;一次结果:异常性疼痛显着减弱。

头痛具有高度致残性,是全球最常见的神经系统疾病之一。尽管头痛的患病率很高,但治疗选择有限。我们最近发现δ阿片受体(DOR)是偏头痛的一个新兴治疗靶点。在这项研究中,我们检查了标志性DOR激动剂SNC80在反映各种头痛疾病的疾病模型中的有效性,包括:慢性偏头痛、创伤后头痛(PTH)、曲坦类药物过度使用头痛(MOH)和阿片类药物诱导的痛觉过敏(OIH)。为了模拟慢性偏头痛,C57BL/6J小鼠接受了已知的人类偏头痛触发器硝酸甘油的慢性间歇性治疗。通过将闭式头部重量下降模型与慢性偏头痛的硝酸甘油模型相结合来模拟PTH。对于MOH和OIH,小鼠分别长期接受舒马曲坦或吗啡治疗。在所有四种模型中都观察到眶周和外周异常性疼痛的发展;SNC80在所有病例中均显著抑制了异常性疼痛。此外,我们还确定了SNC80的慢性日常治疗是否会诱导MOH/OIH,并且我们观察到相对于舒马曲坦或吗啡的有限痛觉过敏。总之,我们的结果表明,尽管病因不同,但DOR激动剂可能对多种头痛疾病有效,从而为头痛提供了一种新的治疗靶点。[1] SNC80在小鼠温水甩尾试验中,静脉注射、静脉注射和腹腔注射后产生了剂量和时间相关的镇痛作用。静脉注射、静脉注射和腹腔注射SNC 80的A50值(和95%置信区间)分别为104.9(63.7-172.7)nmol、69(51.8-92.1)nmol和57(44.5-73.1)mg/kg。在热板试验中,静脉注射SNC 80也产生了与剂量和时间相关的镇痛作用,计算出的A50值(和95%c.i.)为91.9(60.3-140.0)nmol。2. 在小鼠体内测定SNC80的镇痛活性,以研究其体内受体靶标的身份。在这方面,我们假设,由于无法形成μ-δ异聚体,SNC80在缺乏其中一种受体的敲除动物中的活性会降低。采用野生型、μ-KO和δ-KO小鼠来确定μ-和δ-阿片受体对SNC80诱导的镇痛作用的贡献。SNC80通过鞘内注射途径(i.t.)给药于小鼠,并在温水(52.2°C)尾部撤回试验中进行评估(图2),重点关注脊髓,其中体内数据支持受体共定位。选择累积给药方案部分是为了解决SNC-80的溶解度有限的问题,因为三个最高剂量总计300 nmol大大超过了单个5μL鞘内注射体积中可以溶解的化合物量。此外,与之前的非累积给药实验的多次比较显示,结果没有显著差异,验证了该方法。该图(图2)显示了两条不同的剂量-反应曲线,以说明μ-KO小鼠在低剂量下SNC80缺乏效果。在野生型(C57/129)小鼠中,SNC80的ED50=49 nmol,95%置信区间(43-56)。μ-KO小鼠的剂量-反应曲线(根据第二条较高剂量曲线计算)以平行方式右移2.7倍(ED50=131 nmol,95%CI(111-153),图2A)。在野生型(C57BL/6)小鼠中,SNC80显示ED50=53.6 nmol,95%CI(47.0-61.1),在δ-KO小鼠中右移6.1倍,ED50=327 nmol,95%CI(216-494)(约50%MPE,图2B)。结果表明,在μ或δ阿片受体敲除的小鼠中,SNC80的镇痛活性降低。[4] 我们的体内数据还表明,SNC80诱导的镇痛作用是通过脊髓中μ-δ异聚体的选择性激活产生的。μ-KO和δ-KO小鼠SNC80剂量-反应曲线的右移表明,异聚体复合物中的μ-和δ-阿片受体原聚体都有助于野生型小鼠SNC80的镇痛活性。这一结果与先前的研究一致,表明SNC80诱导的镇痛作用同时具有δ和μ阿片受体介导的成分。δ和μ敲除动物中SNC80的效力降低证明了这两种受体的体内贡献,这也是IUPHAR指南建立异聚体复合物的三个具体标准之一。[4] 在Gαo-RGS不敏感的杂合敲除小鼠中,SNC80产生抗痛觉过敏和抗抑郁样作用的效力增强,但SNC80诱导的惊厥没有变化。相反,在Gαo杂合敲除小鼠中,SNC80诱导的抗痛觉过敏被消除,而抗抑郁样作用和抽搐没有改变。在arrestin 3敲除小鼠中没有观察到SNC80诱导的行为变化。在arrestin 2基因敲除小鼠中,SNC80诱导的抽搐增强。 结论和意义:总的来说,这些发现表明,不同的信号分子可能是δ受体相对于其抗痛觉过敏和抗抑郁样作用的惊厥作用的基础[6]。 在本研究中,Gαo-RGSi和Gαo敲除小鼠的δ受体介导的抽搐没有改变。此外,我们之前观察到,在RGS4敲除小鼠中,SNC80诱导的抽搐没有改变(Dripps等人,2017)。总体而言,这些数据可能表明,介导δ受体激动剂诱导的惊厥的信号机制不同于介导抗痛觉过敏和抗抑郁样作用的信号机制。这些行为指标可能受到特定G蛋白亚基、G蛋白非依赖性信号和/或特定脑回路或区域内信号分子选择性表达的不同调节。 为了解决这个问题,我们探讨了SNC80诱导的惊厥是由G蛋白非依赖性、arrestin介导的机制产生的假设。正如Bohn等人(1999)首次表明的那样,我们观察到arrestin 3敲除小鼠吗啡诱导的镇痛作用增强。尽管A类GPCR被认为优先与arrest蛋白3相互作用(Oakley等人,2000),但在arrest蛋白-3敲除小鼠中没有观察到δ受体介导的行为(包括抽搐)的显著变化。应该指出的是,这些数据是急性服用SNC80的结果,arrestin 3可能在调节重复剂量SNC80或其他δ受体激动剂的作用中发挥作用。SNC80的这一观察结果与之前的报告一致,之前的报告发现,小鼠中arrestin 3的缺失不会改变δ受体激动剂的镇痛作用,也不会影响在慢性炎症性疼痛的完全弗氏佐剂(CFA)模型中观察到的δ受体与电压依赖性钙通道的增强偶联(Pradhan等人,2013;Pradhan等,2016)。总体而言,我们的研究结果表明,δ受体介导的抗痛觉过敏、抗抑郁药样作用或抽搐不需要arrestin 3。 在arrestin 2敲除小鼠中,我们观察到SNC80对NTG诱导的热痛觉过敏的反应没有变化。然而,之前的研究表明,SNC80对CFA诱导的机械性痛觉过敏的影响在arrestin 2敲除小鼠中得到了增强(Pradhan等人,2016)。δ受体介导的对这些不同疼痛模式(CFA与NTG;机械与热)的反应可能受到arrestin 2的不同调节。进一步的研究应调查介导不同类型δ受体介导的抗痛觉过敏的信号分子和途径的差异。SNC80的惊厥作用在arrestin 2敲除小鼠中显著增强。在arrestin 2敲除小鼠中,SNC80诱导惊厥的效力增强,表明arrestin 2中起着δ受体介导的惊厥的负调节作用。其次,arrestin 2基因敲除小鼠对单剂量SNC80有多次抽搐反应。 对δ受体介导的抽搐的耐受性通常是急性和长期的(Comer等人,1993;Hong等人,1998)。此外,癫痫发作结束后,SNC80产生的脑电图波形变化恢复到正常的基线活动(Jutkiewicz等人,2006)。据我们所知,这是首次报道啮齿动物对δ受体激动剂产生多种抽搐事件。对这一观察结果的一种可能解释是,arrestin 2的缺失通过阻止δ受体脱敏和/或上调δ受体向细胞膜的运输来产生这些行为变化,从而增强δ受体信号传导(Mittal等人,2013)。然而,在目前的研究中,δ受体介导的抗抑郁样作用和热痛觉过敏在arrestin 2敲除小鼠中没有显著改变。因此,由于区域表达、行为机制和/或信号下调和/或对SNC80惊厥作用的耐受性存在差异,SNC80的行为效应可能受到arrestin 2的不同调节。因此,arrestin 2的缺失可能会使通常会终止的信号通路持续存在并产生多个抽搐事件。未来的工作将研究arrestin 2是否也调节对δ受体激动剂其他行为影响的耐受性。 |

| 酶活实验 |

δ受体饱和结合[6]

在颈椎脱位后将小鼠斩首,立即移除前脑,并如前所述新鲜制备膜(Broom等人,2002a)。未麻醉的组织收集用于限制δ受体数量、构象和/或定位的改变,并且根据美国兽医协会动物安乐死指南,有条件地可接受。用BCA测定试剂盒测定蛋白质浓度。δ受体激动剂[3H]DPDPE的特异性结合如Broom等人(2002a)所述,使用10μM阿片类拮抗剂纳洛酮来确定非特异性结合。反应在26°C下孵育60分钟,并使用MLR‐24收割机通过浸泡在0.1%PEI中的GF/C过滤垫快速过滤停止。通过闪烁计数确定结合[3H]DPDPE,并使用GraphPad Prism 6.02版的非线性回归分析计算B max和K d值。为确保单个值的可靠性,对每只小鼠(每组n=5)的膜进行了三次检测。 |

| 细胞实验 |

细胞内钙释放测定[4]

如前所述,细胞内钙释放测定用于确定SNC80在激活阿片受体时的选择性,但需要稍作修改。简而言之,将稳定表达阿片受体的HEK293细胞在10%CO2气氛中的DMEM(10%FBS,1%P/S)中生长,使用脂质体2000用嵌合G蛋白Δ6-Gqi4-myr瞬时转染,24小时后接种到96孔半面积板中,并在转染后48小时检测细胞内钙释放。在涉及稳定表达嵌合Δ6-Gqi4-myr蛋白的HEK293细胞的实验中,除了阿片受体DNA被瞬时转染,并且共转染细胞中脂质体的量增加了一倍外,程序是相同的。检测采用Flexstation 3装置中的标准探针FLIPR钙染料试剂盒。SNC80游离碱最初溶解在DMSO中。使用DMSO,使最终DMSO浓度最大不超过0.1%v/v,该浓度不会显著改变基础反应的钙通量。为了尽量减少实验的可变性,所有实验都进行了至少三次,四次内部重复,n≥3(12),但表达κ-或μ-κ受体的细胞除外,其中n≥2(8)。对每个平板进行检测控制(空白和标准配体),以消除技术差异并确保反应均匀。 |

| 动物实验 |

Male and female C57BL6/J mice (20-30g) injected with Sumatriptan

10 mg/kg Intraperitoneal injection; once Acute treatment with DOR agonist [1] Eighteen to twenty-four hours after the last drug administration day we determined the effect of SNC80. On this challenge test day, basal hind paw and cephalic mechanical thresholds were determined, after which mice received either vehicle (VEH) or SNC80 (10 mg/kg, ip). SNC80 was diluted to 1 mg/mL in 0.33% 1N HCl/0.9% saline. Post-SNC80 thresholds were assessed 2 hours after basal testing, and 45 minutes after SNC80 injection. Chronic treatment with DOR agonist [1] To determine whether chronic DOR activation caused hypersensitivity similar to MOH, Mice were treated once daily with vehicle, SUMA (0.6 mg/kg, ip), or SNC80 (10 mg/kg, ip) over 11 days. For hind paw experiments, mice were tested on days 1, 3, 5, 7, 9, and 11, and another cohort of mice were tested on days 1 and 11. For cephalic experiments, mice were tested on days 1 and 11, and days 1, 5 and 11 depending on the experiment. Drug stock solutions were dissolved in sterile water and diluted in sterile saline solution with the exception of SNC80, which was initially mixed with 1 equiv of tartaric acid before dissolution in sterile water. Antinociceptive effects of SNC80 were assessed utilizing the warm water (52.5 °C) tail immersion assay. Animals employed were 129sv/C57BL6 mice (μ-opioid receptor WT), μ-KO (−/−) mice on a 129sv/C57BL6 background, C57BL/6 mice (δ-opioid receptor WT), and δ-KO (−/−) mice on a C57BL/6 background, all with ad libitum food access and a 12 hour light/dark cycle. Intrathecal (i.t.) drug administration was accomplished by direct lumbar puncture as modified. A minimum of six mice were assayed at each dose tested, each mouse was used twice, and a total of 48 mice were used in the study. No antinociceptive differences were observed between male and female mice in any of the experiments. Tail flick (TF) latencies were obtained before drug administration to establish a baseline prior to drug treatment; shortly after baseline testing, the lowest dose of drug was injected intrathecally in 5 μL of vehicle, and TF latency was determined 7 min later. Immediately after testing, the subsequent dose of a cumulative dose–response curve was administered, and TF latency was determined 5 min later; three to four doses were thereby administered in rapid succession, and a cumulative dose–response curve was determined. Antagonists were administered 7 min prior to the initial agonist injection. A 12 s cutoff was employed in cases of no detectable response to avoid tissue damage. [4] Forced swim test [6] The forced swim test (FST) is an assay that is widely used to evaluate the antidepressant‐like effects of drugs in rodents (Barkus, 2013). Our experiments were adapted from Porsolt et al. (1977) and performed as previously described (Dripps et al., 2017). Briefly, 60 min after SNC80 (0.1, 0.32, 1, 3.2, 10 or 32 mg·kg−1) or vehicle injection, each mouse was placed in a 4 L beaker filled with 15 cm of 25 ± 1°C water, and its behaviour was recorded for 6 min using a Sony HDR‐CX220 digital camcorder. Videos were analysed by individuals blind to the experimental conditions, and the amount of time the animals spent immobile was quantified. Immobility was defined as the mouse not actively traveling through the water and making only movements necessary to stay afloat. The time the mouse spends immobile after the first 30 s of the assay was recorded. Nitroglycerin‐induced hyperalgesia [6] The NTG‐induced hyperalgesia assay was adapted from Bates et al. (2010) using modifications described in Pradhan et al. (2014) and performed as previously described (Dripps et al., 2017). In brief, male and female mice were used to evaluate NTG‐induced hyperalgesia. Hyperalgesia was assessed by immersing the tail (~5 cm from the tip) in a 46°C water bath and determining the latency for the animal to withdraw its tail with a cut‐off time of 60 s. After determining baseline withdrawal latencies, 10 mg·kg−1 NTG (i.p.) was administered to each animal. Tail withdrawal latency was assessed again 1 h after NTG administration. At 90 min post‐NTG, animals received an injection of SNC80 (0.32, 1, 3.2, 10 or 32 mg·kg−1) or vehicle, and mice were observed continuously in individual cages for 30 min to observe for convulsions (see section below). Tail withdrawal latencies were assessed again 30 min after SNC80 administration. SNC80‐induced convulsions [6] Mice were observed continuously in individual cages for convulsions. Unless otherwise noted, NTG treatment had no significant effect on the frequency or nature of SNC80‐induced convulsions (see Supporting Information). Convulsions were typically composed of a single tonic phase characterized by sudden tensing of the musculature and extension of the forepaws followed by clonic contractions that extended the length of the body. Mice would frequently lose balance and fall on their side, although the so‐called barrel rolling was rarely observed. Convulsions were followed by a period of catalepsy that lasted 2–5 min after which the animals were hyperlocomotive but otherwise indistinguishable from untreated controls. The severity of each convulsion was quantified using the following modified Racine (1972) scale adapted from Jutkiewicz et al. (2006): 1 – teeth chattering or face twitching; 2 – head bobbing or twitching; 3 – tonic extension or clonic convulsion lasting less than 3 s; 4 – tonic extension or clonic convulsion lasting longer than 3 s; and 5 – tonic extension or clonic convulsion lasting more than 3 s with loss of balance. Post‐convulsion catalepsy‐like behaviour was assessed by placing a horizontal rod under the forepaws of the mouse, and a positive catalepsy score was assigned if the mouse did not remove its forepaws after 30 s. Two arrestin 2 knockout mice that received 32 mg·kg−1 SNC80 exhibited sustained convulsions after the observation period and were killed by pentobarbital overdose. SNC80 was dissolved in 1 M HCl and diluted in sterile water to a concentration of 3% HCl. |

| 参考文献 | |

| 其他信息 |

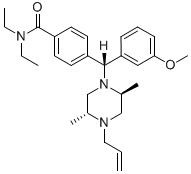

4-[(R)-[(2S,5R)-2,5-dimethyl-4-prop-2-enyl-1-piperazinyl]-(3-methoxyphenyl)methyl]-N,N-diethylbenzamide is a diarylmethane.

Coexpressed and colocalized μ- and δ-opioid receptors have been established to exist as heteromers in cultured cells and in vivo. However the biological significance of opioid receptor heteromer activation is less clear. To explore this significance, the efficacy of selective activation of opioid receptors by SNC80 was assessed in vitro in cells singly and coexpressing opioid receptors using a chimeric G-protein-mediated calcium fluorescence assay, SNC80 produced a substantially more robust response in cells expressing μ-δ heteromers than in all other cell lines. Intrathecal SNC80 administration in μ- and δ-opioid receptor knockout mice produced diminished antinociceptive activity compared with wild type. The combined in vivo and in vitro results suggest that SNC80 selectively activates μ-δ heteromers to produce maximal antinociception. These data contrast with the current view that SNC80 selectively activates δ-opioid receptor homomers to produce antinociception. Thus, the data suggest that heteromeric μ-δ receptors should be considered as a target when SNC80 is employed as a pharmacological tool in vivo.[4] In recent years, the delta opioid receptor has attracted increasing interest as a target for the treatment of chronic pain and emotional disorders. Due to their therapeutic potential, numerous tools have been developed to study the delta opioid receptor from both a molecular and a functional perspective. This review summarizes the most commonly available tools, with an emphasis on their use and limitations. Here, we describe (1) the cell-based assays used to study the delta opioid receptor. (2) The features of several delta opioid receptor ligands, including peptide and non-peptide drugs. (3) The existing approaches to detect delta opioid receptors in fixed tissue, and debates that surround these techniques. (4) Behavioral assays used to study the in vivo effects of delta opioid receptor agonists; including locomotor stimulation and convulsions that are induced by some ligands, but not others. (5) The characterization of genetically modified mice used specifically to study the delta opioid receptor. Overall, this review aims to provide a guideline for the use of these tools with the final goal of increasing our understanding of delta opioid receptor physiology. [5] Background and purpose: GPCRs exist in multiple conformations that can engage distinct signalling mechanisms which in turn may lead to diverse behavioural outputs. In rodent models, activation of the δ opioid receptor (δ-receptor) has been shown to elicit antihyperalgesia, antidepressant-like effects and convulsions. We recently showed that these δ-receptor-mediated behaviours are differentially regulated by the GTPase-activating protein regulator of G protein signalling 4 (RGS4), which facilitates termination of G protein signalling. To further evaluate the signalling mechanisms underlying δ-receptor-mediated antihyperalgesia, antidepressant-like effects and convulsions, we observed how changes in Gαo or arrestin proteins in vivo affected behaviours elicited by the δ-receptor agonist SNC80 in mice. Experimental approach: Transgenic mice with altered expression of various signalling molecules were used in the current studies. Antihyperalgesia was measured in a nitroglycerin-induced thermal hyperalgesia assay. Antidepressant-like effects were evaluated in the forced swim test. Mice were also observed for convulsive activity following SNC80 treatment. [6] One of our aims was to determine if chronic treatment with a DOR agonist would result in OIH/MOH. Interestingly, we found that daily treatment and testing with SNC80 resulted in subsequent hyperalgesia, but that daily treatment alone did not result in increased pain sensitivity, unlike sumatriptan. These results suggest that pharmacological activation of DOR does not produce OIH/MOH, however, if chronic SNC80 is paired with repeated testing then DOR activation might facilitate associative learning resulting in behavioral sensitization. The DOR is expressed in a number of brain regions that can regulate different kinds of learning; including the hippocampus, amygdala, and striatum (Le Merrer et al., 2009; Pellissier et al., 2016; Pradhan et al., 2011). Knockout of DOR results in impairment in object recognition tasks (Le Merrer et al., 2013), as well as deficiencies in place conditioning tasks (Le Merrer et al., 2011). In addition, DORs in the nucleus accumbens shell have been shown to modulate predictive learning (Bertran-Gonzalez et al., 2013; Laurent et al., 2014; Laurent et al., 2015a; Laurent et al., 2015b). We have also previously demonstrated that tolerance to SNC80 is significantly dependent on associative learning (Pradhan et al., 2010; Vicente-Sanchez et al., 2018), and environmental cues related to memory and learning can modulate behavioral outcomes to repeated exposure to opioids (Gamble et al., 1989; Mitchell et al., 2000). Our results should be considered during the development of DOR agonists for headache, as chronic DOR activation could facilitate associated learned behavior in migraineurs. [1] Additionally, our in vitro efficacy data demonstrating selective activation of μ–δ heteromers by SNC80 is further supported by trafficking and binding studies. That these trafficking studies revealed SNC80-induced cointernalization of μ- and δ-opioid receptors is consistent with activation of a μ–δ heteromer as the signaling unit. The present study demonstrates that potent SNC80 activity requires the presence of μ- and δ-opioid receptors both in vitro and in vivo. Considered together, and in light of prior studies, the combined results presented here suggest that SNC80, in vivo, interacts selectively with the δ-protomer of the μ–δ heteromer, thereby leading to the activation of the heteromeric complex. While this conclusion does not invalidate previous research demonstrating that SNC80 is a δ-selective ligand in receptor homomer models, it strongly suggests the involvement of the μ–δ heteromer as a selective target in the signaling pathway. The implications of μ–δ receptor heteromers as a target for SNC80 suggest a more complex role for this ligand in vivo, given that μ-selective ligands (based on binding) also target μ–δ heteromers but via the μ-protomer. It therefore appears that the output of the agonist depends on which protomer in the μ–δ heteromer is targeted for activation. The fact that, unlike μ-agonists, SNC80 does not produce physical dependence illustrates the complexity of the heteromeric system and suggests that different signaling pathways are dependent on the protomer that is activated in the μ–δ heteromeric complex.[4] |

| 分子式 |

C28H39N3O2

|

|---|---|

| 分子量 |

449.64

|

| 精确质量 |

449.304

|

| 元素分析 |

C, 74.80; H, 8.74; N, 9.35; O, 7.12

|

| CAS号 |

156727-74-1

|

| PubChem CID |

123924

|

| 外观&性状 |

Off-white to light yellow solid powder

|

| 密度 |

1.0±0.1 g/cm3

|

| 沸点 |

564.8±50.0 °C at 760 mmHg

|

| 熔点 |

122-123ºC

|

| 闪点 |

295.4±30.1 °C

|

| 蒸汽压 |

0.0±1.5 mmHg at 25°C

|

| 折射率 |

1.545

|

| LogP |

3.37

|

| tPSA |

36.02

|

| 氢键供体(HBD)数目 |

0

|

| 氢键受体(HBA)数目 |

4

|

| 可旋转键数目(RBC) |

9

|

| 重原子数目 |

33

|

| 分子复杂度/Complexity |

614

|

| 定义原子立体中心数目 |

3

|

| SMILES |

C=CCN1C[C@H](C)N(C[C@H]1C)[C@H](C2=CC=C(C=C2)C(=O)N(CC)CC)C3=CC(=CC=C3)OC

|

| InChi Key |

KQWVAUSXZDRQPZ-UMTXDNHDSA-N

|

| InChi Code |

InChI=1S/C28H39N3O2/c1-7-17-30-19-22(5)31(20-21(30)4)27(25-11-10-12-26(18-25)33-6)23-13-15-24(16-14-23)28(32)29(8-2)9-3/h7,10-16,18,21-22,27H,1,8-9,17,19-20H2,2-6H3/t21-,22+,27-/m1/s1

|

| 化学名 |

4-[(R)-[(2S,5R)-2,5-dimethyl-4-prop-2-enylpiperazin-1-yl]-(3-methoxyphenyl)methyl]-N,N-diethylbenzamide

|

| 别名 |

SNC80; SNC-80; 156727-74-1; 4-(alpha-(4-allyl-2,5-dimethyl-1-piperazinyl)-3-methoxybenzyl)-N,N-diethylbenzamide; 4-[(R)-[(2S,5R)-2,5-dimethyl-4-prop-2-enylpiperazin-1-yl]-(3-methoxyphenyl)methyl]-N,N-diethylbenzamide; Benzamide, 4-[(R)-[(2S,5R)-2,5-dimethyl-4-(2-propen-1-yl)-1-piperazinyl](3-methoxyphenyl)methyl]-N,N-diethyl-; CHEMBL13470; SNC80

|

| HS Tariff Code |

2934.99.9001

|

| 存储方式 |

Powder -20°C 3 years 4°C 2 years In solvent -80°C 6 months -20°C 1 month |

| 运输条件 |

Room temperature (This product is stable at ambient temperature for a few days during ordinary shipping and time spent in Customs)

|

| 溶解度 (体外实验) |

DMSO: ~33.33 mg/mL (~74.1 mM)

|

|---|---|

| 溶解度 (体内实验) |

配方 1 中的溶解度: ≥ 3.33 mg/mL (7.41 mM) (饱和度未知) in 10% DMSO + 40% PEG300 + 5% Tween80 + 45% Saline (这些助溶剂从左到右依次添加,逐一添加), 澄清溶液。

例如,若需制备1 mL的工作液,可将100 μL 33.3 mg/mL澄清DMSO储备液加入400 μL PEG300中,混匀;然后向上述溶液中加入50 μL Tween-80,混匀;加入450 μL生理盐水定容至1 mL。 *生理盐水的制备:将 0.9 g 氯化钠溶解在 100 mL ddH₂O中,得到澄清溶液。 配方 2 中的溶解度: ≥ 3.33 mg/mL (7.41 mM) (饱和度未知) in 10% DMSO + 90% (20% SBE-β-CD in Saline) (这些助溶剂从左到右依次添加,逐一添加), 澄清溶液。 例如,若需制备1 mL的工作液,可将 100 μL 33.3 mg/mL 澄清 DMSO 储备液加入 900 μL 20% SBE-β-CD 生理盐水溶液中,混匀。 *20% SBE-β-CD 生理盐水溶液的制备(4°C,1 周):将 2 g SBE-β-CD 溶解于 10 mL 生理盐水中,得到澄清溶液。 View More

配方 3 中的溶解度: ≥ 3.33 mg/mL (7.41 mM) (饱和度未知) in 10% DMSO + 90% Corn Oil (这些助溶剂从左到右依次添加,逐一添加), 澄清溶液。 1、请先配制澄清的储备液(如:用DMSO配置50 或 100 mg/mL母液(储备液)); 2、取适量母液,按从左到右的顺序依次添加助溶剂,澄清后再加入下一助溶剂。以 下列配方为例说明 (注意此配方只用于说明,并不一定代表此产品 的实际溶解配方): 10% DMSO → 40% PEG300 → 5% Tween-80 → 45% ddH2O (或 saline); 假设最终工作液的体积为 1 mL, 浓度为5 mg/mL: 取 100 μL 50 mg/mL 的澄清 DMSO 储备液加到 400 μL PEG300 中,混合均匀/澄清;向上述体系中加入50 μL Tween-80,混合均匀/澄清;然后继续加入450 μL ddH2O (或 saline)定容至 1 mL; 3、溶剂前显示的百分比是指该溶剂在最终溶液/工作液中的体积所占比例; 4、 如产品在配制过程中出现沉淀/析出,可通过加热(≤50℃)或超声的方式助溶; 5、为保证最佳实验结果,工作液请现配现用! 6、如不确定怎么将母液配置成体内动物实验的工作液,请查看说明书或联系我们; 7、 以上所有助溶剂都可在 Invivochem.cn网站购买。 |

| 制备储备液 | 1 mg | 5 mg | 10 mg | |

| 1 mM | 2.2240 mL | 11.1200 mL | 22.2400 mL | |

| 5 mM | 0.4448 mL | 2.2240 mL | 4.4480 mL | |

| 10 mM | 0.2224 mL | 1.1120 mL | 2.2240 mL |

1、根据实验需要选择合适的溶剂配制储备液 (母液):对于大多数产品,InvivoChem推荐用DMSO配置母液 (比如:5、10、20mM或者10、20、50 mg/mL浓度),个别水溶性高的产品可直接溶于水。产品在DMSO 、水或其他溶剂中的具体溶解度详见上”溶解度 (体外)”部分;

2、如果您找不到您想要的溶解度信息,或者很难将产品溶解在溶液中,请联系我们;

3、建议使用下列计算器进行相关计算(摩尔浓度计算器、稀释计算器、分子量计算器、重组计算器等);

4、母液配好之后,将其分装到常规用量,并储存在-20°C或-80°C,尽量减少反复冻融循环。

计算结果:

工作液浓度: mg/mL;

DMSO母液配制方法: mg 药物溶于 μL DMSO溶液(母液浓度 mg/mL)。如该浓度超过该批次药物DMSO溶解度,请首先与我们联系。

体内配方配制方法:取 μL DMSO母液,加入 μL PEG300,混匀澄清后加入μL Tween 80,混匀澄清后加入 μL ddH2O,混匀澄清。

(1) 请确保溶液澄清之后,再加入下一种溶剂 (助溶剂) 。可利用涡旋、超声或水浴加热等方法助溶;

(2) 一定要按顺序加入溶剂 (助溶剂) 。

|

|

|

|

|